In the United States, federal and state laws prohibit prospective employers from asking certain questions that are not related to the job for which they are hiring; however, most interviewers are not deliberately trying to discriminate against job applicants. In fact, many illegal* interview questions come out unintentionally in a conversational tone. As an example, an interviewer could start the interview with some ice breaker type questions and say, “You have such an interesting name! What’s the origin?” Outside of an interview, this would be a pretty innocuous question; however, within an interview, it could be construed as trying to ascertain your nationality.

Personal information like your heritage, religion, age, and marital status can very subtly sneak into an interview. Here are a few more examples: y

Subject: Nationality

Illegal Questions: Are you a U.S. citizen? Where were you born? Is English your first language?

Legal to Ask: Are you authorized to work in the United States on a full-time basis? What languages do you speak and what is your proficiency level? (This can also be tested by the interview itself and/or a written exam.)

Subject: Marital/Family Status

Illegal Questions: Are you married? Are you planning to have children? How many kids do you have? What are your child care arrangements?

Legal to Ask: Would you be willing to relocate if necessary? Are you willing to travel as stated in the position description?

Subject: Disabilities

Illegal Questions: Do you have a disability? Have you had any recent illnesses or operations?

Legal to Ask: Are you able to perform the essential functions of this position with or without reasonable accommodations?

Subject: Age

Illegal Questions: How old are you? What is your birthdate? When did you graduate from college?

Legal to Ask: Are you over the age of 18?

Subject: Affiliations

Illegal Questions: What religious holidays do you celebrate? What clubs/organizations do you belong to?

Legal to Ask: Are you available to work Sundays (if the position notes this)?

What should you do if one of these questions gets asked during your interview? It can be a challenge to weigh your options quickly while you are still face to face with the interviewer. So, if there is an area which is of specific concern for you, try to prepare some possible responses. Here are four different options:

- Simply answer the question. Only choose this option if you are truly comfortable providing that information and don’t personally feel that it could cause an issue for you.

- Answer the question with a question of your own. You could say, “I’m happy to try and answer that question for you, but can you help me understand how that relates to this job first?”

- Don’t answer directly, but respond to the intent of the question. For example, if the interviewer asks if you are a U.S. citizen, you can respond by saying, “I think you are meaning to ask if I am legally authorized to work here and the answer is yes.”

- Refuse to answer the question. This last resort should only be utilized for a very egregious question.

Knowing in advance what kinds of illegal questions are apt to sneak into an interview and how you feel about answering them should be a part of your interview preparation. This can help you quickly diffuse an uncomfortable situation should it arise. Beyond what's legal, there are also disclosures that can make you feel uncomfortable discussing in a professional setting. We will be touching on some of these issues in future blog posts.

* Illegal interview questions, while not illegal in the strictest meaning, do have great potential to open a company or organization up to being held liable in a discrimination law suit.

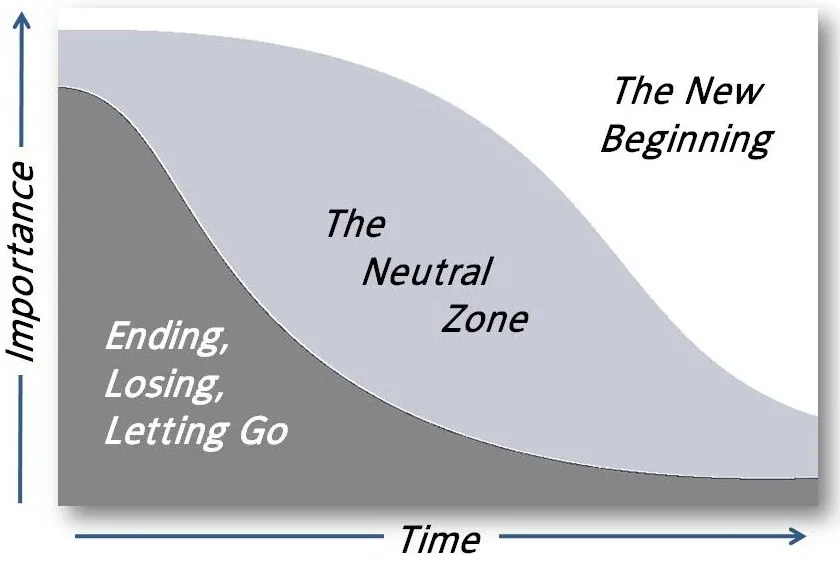

1. Ending, Losing, and Letting Go

At this stage, you are probably experiencing a situational change which can trigger a psychological transition. Change can signal the start of a new opportunity which also means the end of an old opportunity. This could mean the temporary end of feeling sure of your daily tasks or the end of associating with a (comfortable) peer group. Even if this ending is a positive development, it could cause you to feel uncertain and question yourself and your values or abilities. As you are letting go of your previous experience, make sure you solicit the support and resources offered at NIH. The Office of Intramural Training and Education (OITE) offers many workshops and individual counseling appointments to help you get oriented and connected to the resources and opportunities at NIH. You may learn more at www.training.nih.gov.

2. The Neutral Zone

The neutral zone or transition period can be a time of creative exploration and discovery while you are clarifying your options and goals. This is a great time to explore new ways of thinking about your career and to connect to people who are working as professionals in fields of interest to learn about their work. In order to learn more about your options and connect, you may want to start talking with people in informational interviews. Sometimes trainees find it helpful to plan how to set up informational interviews with a career counselor, especially if this is a new concept. If your experience has been primarily at the bench, you may also want to explore professional involvement in a FELCOM Committee, a professional society, or committees in your IC or community.

3. The New Beginning

The new beginning is the final step in the transition process. It is usually marked by a decrease in anxiety, an increase in enthusiasm, and a clearer vision on how your recent change fits into your long- term plans. This might include starting medical school, a PhD program or moving on to a career as a faculty member, PI, science policy analyst, specialist in technology transfer, grants administrator, and beyond.

Most people will go through each phase during a change; however, remember that each individual responds to change very differently. You might find that you breeze through transitions pretty quickly while others may struggle with each step. No matter what stage you are in related to your career goals and transitions, please take a look at the resources and services to support you at www.training.nih.gov.

William Bridges' book, Managing Transitions: Making the Most of Change, offers suggestions about dealing with transitions and coping with change. You can find this book in most public libraries and it is also available in the OITE Career Library on the second floor of Building 2.

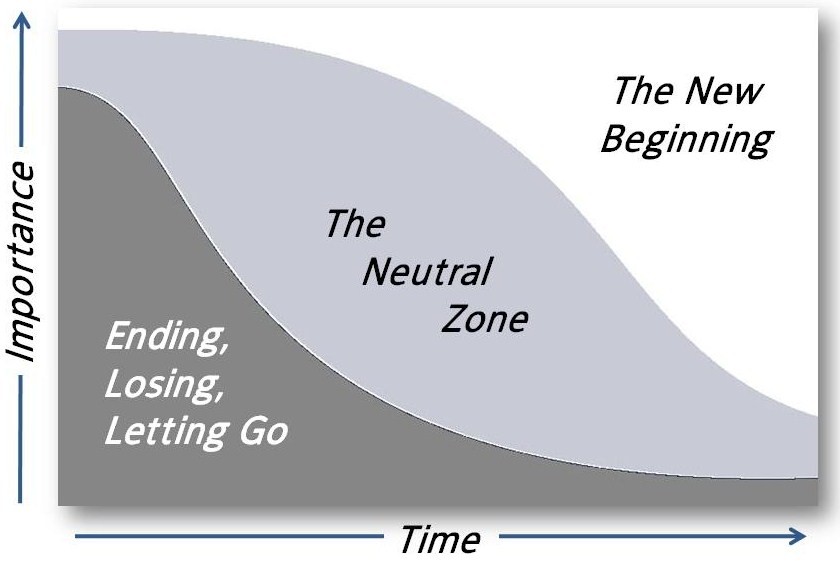

1. Ending, Losing, and Letting Go

At this stage, you are probably experiencing a situational change which can trigger a psychological transition. Change can signal the start of a new opportunity which also means the end of an old opportunity. This could mean the temporary end of feeling sure of your daily tasks or the end of associating with a (comfortable) peer group. Even if this ending is a positive development, it could cause you to feel uncertain and question yourself and your values or abilities. As you are letting go of your previous experience, make sure you solicit the support and resources offered at NIH. The Office of Intramural Training and Education (OITE) offers many workshops and individual counseling appointments to help you get oriented and connected to the resources and opportunities at NIH. You may learn more at www.training.nih.gov.

2. The Neutral Zone

The neutral zone or transition period can be a time of creative exploration and discovery while you are clarifying your options and goals. This is a great time to explore new ways of thinking about your career and to connect to people who are working as professionals in fields of interest to learn about their work. In order to learn more about your options and connect, you may want to start talking with people in informational interviews. Sometimes trainees find it helpful to plan how to set up informational interviews with a career counselor, especially if this is a new concept. If your experience has been primarily at the bench, you may also want to explore professional involvement in a FELCOM Committee, a professional society, or committees in your IC or community.

3. The New Beginning

The new beginning is the final step in the transition process. It is usually marked by a decrease in anxiety, an increase in enthusiasm, and a clearer vision on how your recent change fits into your long- term plans. This might include starting medical school, a PhD program or moving on to a career as a faculty member, PI, science policy analyst, specialist in technology transfer, grants administrator, and beyond.

Most people will go through each phase during a change; however, remember that each individual responds to change very differently. You might find that you breeze through transitions pretty quickly while others may struggle with each step. No matter what stage you are in related to your career goals and transitions, please take a look at the resources and services to support you at www.training.nih.gov.

William Bridges' book, Managing Transitions: Making the Most of Change, offers suggestions about dealing with transitions and coping with change. You can find this book in most public libraries and it is also available in the OITE Career Library on the second floor of Building 2.