Analyzing the NIH Alumni Database: Where are our NIH postdocs going?

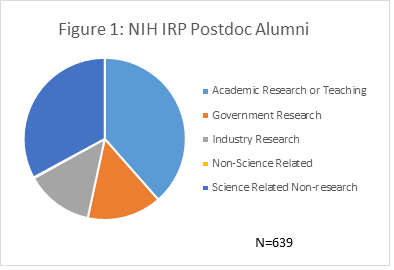

In the OITE we are often asked about the career paths of former postdocs. While we do not conduct mandatory exit surveys, we do have some data from the OITE NIH Alumni Database. This database is populated as fellows leave the NIH. To date it contains about 1100 entries. Of those, 639 contain career information that we have been able to analyze. Caveat: this information is only from former trainees who have voluntarily created entries in the database; it does not capture the full range nor percentage of actual career paths*.

We began by comparing data on our intramural research program (IRP) alumni to the data published in the 2012 NIH Biomedical Research Workforce Working Group Report (BWF). This report analyzed a post-training workforce of 128,000 people in terms of six categories. Academic Research/Teaching accounted for 43% of the workforce, followed by Science-Related, non-Research (individuals employed by industry, government, non-profits who do not conduct research) and Industrial Research at 18% each. The Non-Science-Related workforce employed 13%, and Government Research accounted for an additional 6%. Two percent reported they were unemployed.

In Figure 1 we show that fractions of IRP alumni who have continued in Academic/Research Teaching (39%) and Industrial Research (14%) were similar to those in the national BWF survey. However, far more IRP alumni continued in Government Research (15% of NIH IRP vs 6% in the national survey) and Science-Related, non-Research (33% of NIH IRP vs 18% for the national survey) careers, while far fewer went on to careers in non-Science-Related professions (< 1% vs 13%). No one in our alumni database reported that they were unemployed.

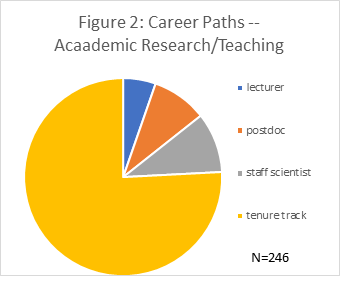

Our percentage of alumni staying in government research is higher than the national average (15% vs. 6%). This is not surprising that some fellows choose to stay as staff scientists or become tenure track within the IRP. The information of what careers are considered non-science related was difficult to find. Our analysis of alumni careers suggests that science-related non-research careers are more common than the national average. Dissecting the Academic Research/Teaching data provides us with more information about what types of positions are held in this sector, Figure 2.

This category includes only positions directly associated with research or teaching; careers in academic institutions in offices such as tech transfer, policy, academic affairs, etc. are counted in the Science-Related, Non-Research category. Three-quarters of alumni in this sector are in academic tenure-track or tenured positions.In fact 192 total alumni in the database are tenured or tenure track faculty (185 are in academics and 7 in government research). From this data we predict that 30% of IRP alumni have tenured or tenure track faculty positions.

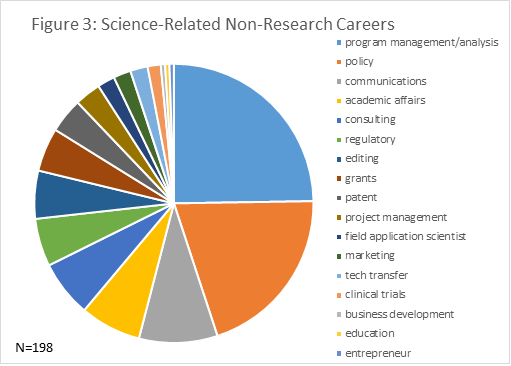

The data for the Science-Related Non-research careers demonstrates the breadth of career options that are available for PhD-trained scientists, Figure 3. We binned careers based on the job titles that were submitted to the alumni database. Discerning the exact jobs of the 25% of reported careers in program management/analysis is challenging. The titles range from program coordinator to manager, director and advisor. Similarly, it is very likely that the 5% of alumni that report working in grants (as program officers, analysts, or review) is low due to the lack of precision in the job titles within the program management/analysis category. The data still provide evidence that program administration (making sure that science runs) is a common career choice. Science policy is a career path selected by 20% NIH of reported alumni. These careers are in all sectors, but are mainly spilt between the Federal government and non-profits (i.e., professional societies). Other career choices reflected in Figure 3 show the breath of career choices for NIH postdocs.

If you want any addiional information about the careers in these categories we suggest that you explore the alumni database. As a current fellow with an OITE account you can search the database: https://www.training.nih.gov/alumni. Additionally, you can use the contact information in the alumni database to set up informational interviews as you plan your career post-NIH.

In 2017 we hope you will help us with this data project! Are you an NIH alum? If so, join the database or update your earlier submission. Last year around 800 people logged-in to the database and updated their information. But we still have too many gaps. 460 postdocs, for example, have an alumni database account that include no information about their current position. Only have ~20% of our postdocs* actually contribute to the database. The OITE really does want to know where you are! Current and future postdocs want to be able to see career trends and how training at the NIH might influence their career choices. So join the database or update your record now: https://www.training.nih.gov/alumni/register

*The database was built in June 2010. We estimate that 800 postdocs per year leave the NIH. Therefore the maximum sample size could be ~5200 alumni. With 1100 reporting that represents 21.2% of the potential sample size.

To learn about the full range of services and programs offered by the Office of Intramural Training and Education, visit us at https://www.training.nih.gov.